Africa's Legacy in

Mexico

A Legacy of Slavery

|

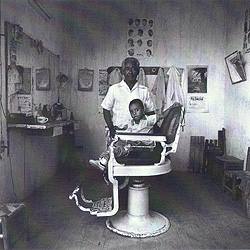

"Barber Shop," Pinotepa

Nacional, Oaxaca, Mexico, 1990

A LEGACY OF SLAVERY

Colin A. Palmer

When I arrived in Mexico about two decades

ago to begin research on the early history of Africans and their descendants

there, a young student politely told me that I was embarking on a wild goose

chase. Mexico had never imported slaves from Africa, he said, fully certain

that the nation's peoples of African descent were relatively recent arrivals.

This lack of knowledge about Mexico's African peoples has not changed

much over time. A short while ago a Mexican engineer, himself of African

descent, told me adamantly that the country's blacks were the descendants

of escaped slaves from North America and Cuba. These fugitives, he proudly

proclaimed, had sought and found sanctuary in free Mexico.

The historical record, of course, tells another story. In the sixteenth

century, New Spain--as Mexico was then called--probably had more enslaved

Africans than any other colony in the Western Hemisphere. Blacks were present

as slaves of the Spaniards as early as the 1520s. Over the approximately

three hundred years it lasted, the slave trade brought about 200,000 Africans

to the colony. Many blacks were born in Mexico and followed their parents

into slavery. Not until 1829 was the institution abolished by the leaders

of the newly independent nation.

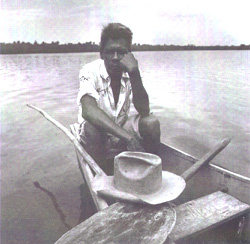

"Man & Canoe," Corralero,

Oaxaca, Mexico, 1987

African labor was vital to the Spanish colonists. As indigenous peoples

were killed or died from European diseases, blacks assumed a disproportionate

share of the burden of work, particularly in the early colonial period.

African slaves labored in the silver mines of Zacatecas, Taxco, Guanajuato,

and Pachuca in the northern and central regions; on the sugar plantations

of the Valle de Orizaba and Morelos in the south; in the textile factories

("obrajes") of Puebla and Oaxaca on the west coast and in Mexico

City; and in households everywhere. Others worked in skilled trade or on

cattle ranches. Although black slaves were never more than two percent of

the total population, their contributions to colonial Mexico were enormous,

especially during acute labor shortages.

Wherever their numbers permitted, slaves created networks that allowed

them to cope with their situation, give expression to their humanity, and

maintain a sense of self. These networks flourished in Mexico City, the

port city of Veracruz, the major mining centers, and the sugar plantations,

allowing Africans to preserve some of their cultural heritage even as they

forged new and dynamic relationships. Although males outnumbered females,

many slaves found spouses from their own or other African ethnic groups.

Other slaves married or had amorous liaisons with the indigenous peoples

and to a lesser extent the Spaniards. In time, a population of mixed bloods

emerged, gaining demographic ascendancy by the mid-eighteenth century. Known

as "mulattos," "pardos," or "zambos," many

of them were either born free or in time acquired their liberty.

As in the rest of the Americas, slavery in Mexico exacted a severe physical

and psychological price from its victims. Abuse was a constant part of a

slave's existence; resisting oppression often meant torture, mutilation,

whipping, or being put in confinement. Death rates were high, especially

for slaves in the silver mines and on the sugar plantations. Yet, for the

most part, their spirits were never broken and many fled to establish settlements

("palenques") in remote areas of the country.

These fugitives were a constant thorn in the side of slave owners. The

most renowned group of "maroons," as they were called, escaped

to the mountains near Veracruz. Unable to defeat these intrepid Africans,

the colonists finally recognized their freedom and allowed them to build

and administer their own town. Today, their leader, Yanga, remains a symbol

of black resistance in Mexico.

Other slaves rebelled or conspired to. The first conspiracy on record

took place in 1537, and these assaults on the system grew more frequent

as the black population increased.

Regardless of the form it took--escape or rebellion--resistance demonstrated

an angry defiance of the status quo and the slaves' desire to reclaim their

own lives. As such, black resistance occupies a special place in Mexico's

revolutionary tradition, a tradition that is a source of pride for many

Mexicans.

Beyond that, Africans in Mexico left their cultural and genetic imprint

everywhere they lived. In states such as Veracruz, Guerrero, and Oaxaca,

the descendants of Africa's children still bear the evidence of their ancestry.

No longer do they see themselves as Mandinga, Wolof, Ibo, Bakongo, or members

of other African ethnic groups; their self identity is Mexican, and they

share much with other members of their nation-state.

Yet their cultural heritage has not entirely disappeared. Some African

traditions survive in song, music, dance, and other ways. But much has changed

since slavery ended, and it is difficult for a small minority to maintain

its traditions in a constantly changing society.

As their ancestors did, the few remaining persons who are visibly of

African descent continue to be productive members of society. But history

has not been kind to the achievements of African peoples in Mexico. It is

only within recent times that their lives have been studied and their contributions

to Mexican society illuminated. Suffice it to say that contemporary black

Mexicans can claim this proud legacy and draw strength from it, even as

they become a shrinking part of their country's peoples.

|