Africa's Legacy in

Mexico

Mexico's Third Root

|

MEXICO'S THIRD ROOT MEXICO'S THIRD ROOT

Luz Maria Martinez Montiel

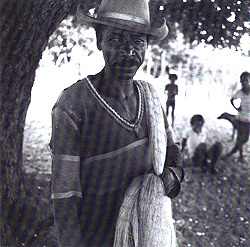

Wherever people gather in the poor fishing

villages of Costa Chica on Mexico's southwest coast--in their homes, on

the streets, in the town squares during festivals--someone is likely to

step forward and start singing. These impromptu performers regale their

audience with songs of romance, tragedy, comedy, and social protest, all

inspired by local events and characters. At the heart of the songs, called

"corridos," is a sense of human dignity and a desire for freedom

rooted in the lives and history of the people of Costa Chica, many of whom

are descendants of escaped slaves.

The corridos reflect oral traditions inherited from Africa. The words are

improvised, and a corrido that brings applause is apt to be committed to

memory, to be sung again and again as an oral chronicle of local life. The

lyrics are also rich in symbols, a tradition that may have started when

singers among the first slaves invented "code words" to protest

the cruelties of their  masters. masters.

The African imprint in Costa Chica is not confined to music. For the "Dance

of the Devil," performed during Holy Week in the streets of Collantes,

Oaxaca, dancers wear masks that show the clear influence of Africa. And

down on the docks, fishermen employ methods of work that may have been brought

centuries ago from the coast of West Africa.

The Spanish colonists took full advantage of technology that Africans had

developed for work in the tropics and adapted and improved in the New World.

Yet today, many African contributions to advancing the technologies of fishing,

agriculture, ranching, and textile-making in Mexico remain unappreciated.

Although strongest in black enclaves like Costa Chica, the African presence

pervades Mexican culture. In story and legend, music and dance, proverb

and song, the legacy of Africa touches the life of every Mexican.

Still, it is difficult to single out any one influence as "purely"

African. Certainly, the African presence in Mexico has never been monolithic.

Although most slaves were brought from West Africa, they represented many

ethnic groups (the Cafi, the Arara, the Carabali, the Wolof, and the Mandinga,

to name a few), each with a different culture and world view. Today, after

five hundred years of blending with the traditions of Indians and Europeans,

it has become nearly impossible to trace the specific contributions of any

of these groups.

Compounding the difficulty is the fact that the African elements in Mexico's

culture are not acknowledged as they are in other countries of the Americas.

In fact, "el mestizaje," the official ideology that defines Mexico's

culture as a blend of European and indigenous influences, completely ignores

the contributions of the nation's "third root." Africans and their

descendants, nearly invisible in the Spanish chronicles of the colonial

period, continue to receive little attention in the official history of

Mexico. So it is no surprise that blacks, who live primarily in poor, rural

areas where the level of education is very low, lack a clear consciousness

of their African heritage.

To an extent, geography has shaped the heritage of Mexico's black communities.

The isolation of the west coast and the mountains, which offered sanctuary

to escaped slaves, also preserved many elements of African tradition. On

the other hand, the Gulf Coast region, especially the port of Veracruz,

was a crossroads where Mexico's indigenous culture blended with myriad influences

from Africa, Europe, South America, and especially the Caribbean. In this

variegated mixture, it is sometimes difficult to isolate the African presence.

As in the past, blacks on the Gulf Coast are more likely to trace the

origins of their lineage to the Caribbean. The people on the west coast

and in the mountains, however, have lately begun to acknowledge their links

to Africa and to their slave past. In part, this is in response to recent

ethnographic, folkloric, and historical studies as well as to frequent visits

by scholars to these regions. It may be as well that the stress of increasing

contact with other peoples--and with immigrants who now come to exploit

their land and labor--has fostered a need among these groups for a self

identity defining them as "the blacks from the coast."

It is a fact that economic stresses compel ethnic groups in sudden contact

with outsiders to either reinforce their traditions or capitulate to the

attractions that cultural homogenization has to offer. This is how cultural

groups are depersonalized and their traditional values lost. Hopefully,

the blacks of Costa Chica and elsewhere in Mexico will come to find new

meaning in the traditions that have sustained them for centuries. Mexico

will be that much the richer for it.

|