![]()

Political parties introduced to American presidential elections several

informal practices that have no constitutional definition. Instead, they

complement the Constitution by providing an effective means to select candidates

of proven ability and national reputation.

Early on, presidential candidates were chosen by a few influential party

members who assembled in state and congressional caucuses. It became clear

by the late 1830s, however, that this process did not appear democratic

enough to the thousands of newly enfranchised voters. Thus was born the

curiously American ritual of the quadrennial national party convention.

From the beginning, conventions were highly stylized and emotive affairs,

partly reminiscent of religious revival meetings and attended by an enthusiastic

cross section of the party's faithful. A convention's primary function was

not always to select a candidate but to reconcile competing factions and

unite the party behind the nominee. As part of this reconciliation process,

convention delegates drafted a statement of party principles – a platform – that

represented the views of those assembled. Candidates would pledge to uphold

their party platforms, but seldom have elected presidents used these principles

as a basis for enacting their legislative agendas.

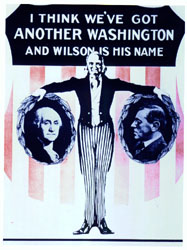

Woodrow Wilson campaign poster, 1912.

National conventions became less important in the candidate selection

process by the mid-twentieth century, as reformers within both major parties

advocated a series of state primaries as a means of more actively involving

the party rank and file. Once they became widely adopted, primaries virtually

guaranteed to establish major party nominees well before the national conventions

took place.

American political parties also transformed the national presidential campaign

into a colorful spectacle. An eclectic mixture of American popular culture

and politics, the national campaign pitted the major parties in a titanic

battle to market their respective candidates to the wider electorate.

Around 1840, national campaigns began to surround the presidential election

process in an atmosphere of unrestrained hoopla. The party faithful marched

in torchlight parades; sang official campaign songs; devoured adoring campaign

biographies; subscribed to party newspapers; and displayed buttons, banners,

ashtrays, mugs, and every manner of memorabilia emblazoned with the name

and image of their candidate.

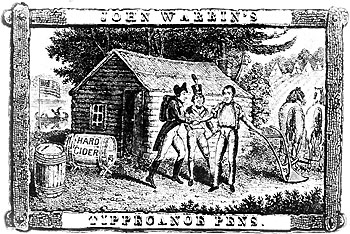

Whig Candidate William Henry Harrison is portrayed as a humble farmer

and military hero in this pen box illustration (1840).

These seemingly frivolous efforts were directed toward a very serious

end: convincing as many voters as possible to cast their ballot for the

party's nominee. Because of peculiarities in the Electoral College system,

a difference of only a few thousand popular votes was often enough to garner

a candidate the total count of a state's electoral votes – and possibly the

presidency.

educate@si.edu