Achelous, the river god, was by far the strongest in the region. But Dejanira’s beauty was known everywhere, so it wasn’t long before Hercules came to Calydon to try his luck.

Hercules was the strongest mortal in the world, but Achelous, being a god, had some advantages over him. He could change his shape at will. He could become a snake that curved like the winding river. He could become a bull that roared like the roaring river. And when he was a bull he could tear the very earth with his massive horns, just as the river carved away the land when it overflowed its banks.

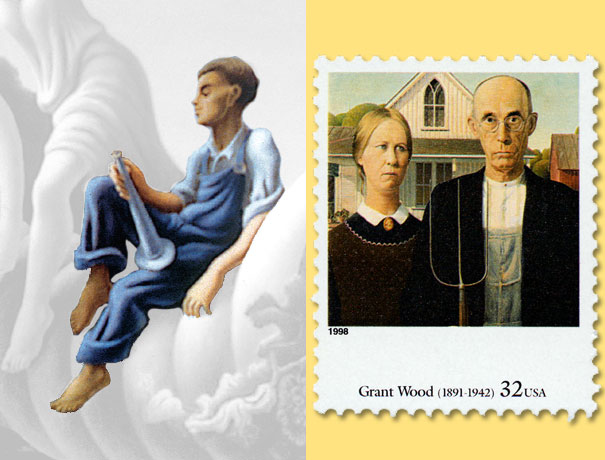

When Hercules came to town, all other suitors withdrew. He alone would wrestle Achelous for the hand of Dejanira.

“Here is Hercules,” Achelous said to the king. “He is a stranger, from distant Thebes. Do you want a stranger for a son-in-law? You and I are neighbors. You know me well. So often has my river flooded your fields and crops, fields and crops that are Dejanira’s too. Her land and my flooding river have already joined. I feel as if you and I are already family!”

Hercules, in contrast, was a man of very few words. He listened patiently and politely and then gave his answer: he grabbed the river god, threw him, and pinned him to the ground. As Achelous would later say, “It was as if a mountain had fallen on me. Hercules was a mountain of a man.”

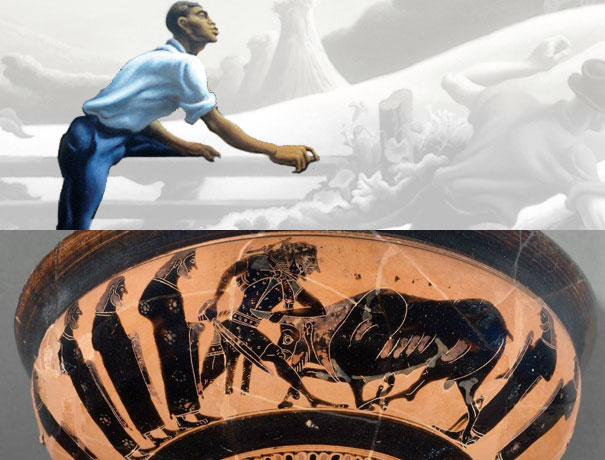

The god saw he could not beat Hercules in a regulation wrestling match. It was then that he took the form of a snake that slithered out of the strong man’s arms. He coiled himself and gave a hiss. Hercules laughed and spoke for the first time.

“A snake!” he said. “Is that the best you can do? I’ve been killing snakes since I was a babe in the crib.”

What might have seemed a wild boast was entirely true, and Achelous knew it. Hercules’s famous first feat in life was strangling two snakes that had crawled into his crib.

Achelous the snake decided to become Achelous the furious bull. He lowered his broad head to point his sharp horns at Hercules. He scratched at the dirt and then he charged. The crowd let out a gasp.

But to a man like Hercules, the horns of a bull were just two convenient handles. He seized Achelous by both of them and flipped him to the ground. He then gave a mighty jerk to one of the horns. It snapped off.

Hercules won the match and won Dejanira’s hand in marriage. And the people of Calydon won as well. The goddess named Plenty ordered that the bull’s broken horn be filled with all the fruits and vegetables of the harvest. It became the Cornucopia, or Horn of Plenty. With one horn missing, Achelous lost much of his power to flood the kingdom.

If you are ever in Greece, you might go to see his river. It is in the rainiest part of a fairly dry country. It is still called the Achelous. You would find a quiet stream that flows along fertile fields—fields that are safe for farming.

Tap on the image to zoom back in.

Tap on the image to zoom back in.