|

The association with European scientists was not

just symbolic. Soon after the Revolutionary War, Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, wrote to a professor at Edinburgh that “the members of the republic of science all belong to the same family. What has physic [medicine] to do with taxation or independence?”

Franklin, too, believed that

science transcended conflicts between nations. During the war

he issued a “passport” for Captain Cook, the British

explorer, who had set out on a voyage before the war began. He addressed a letter to all American ships,

recommending that Cook’s ship not be seized, for “the increase of geographical knowledge facilitates the

communication between distant nations . . . whereby

the common enjoyments of human life are multiplied and augmented, and science of other kinds increased

to the benefit of mankind in general.”

The “republic” also transcended class lines. The

social backgrounds of American men of science ranged from the Boston Puritan establishment and the Southern planter aristocracy to that of Franklin himself.

|

|

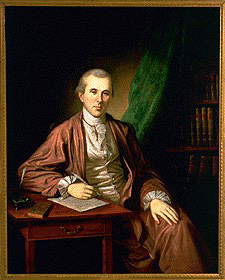

Benjamin Rush was interested in earthquakes as a medical as well as a geological subject. He examined a geological subject. He examined them as a possible cause of disease.

Benjamin Rush, by Charles Willson Peale, 1783 and 1786. Winterthur Museum; gift of Mrs. Julia B. Henry, 1959.

|